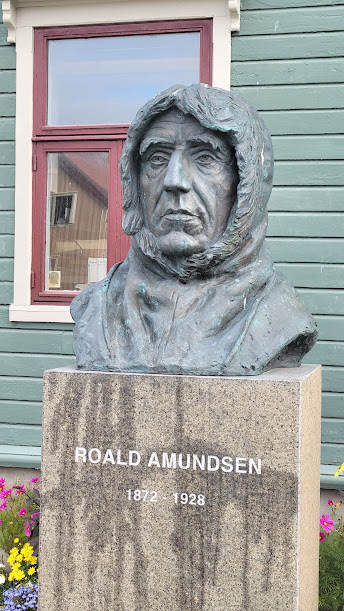

You can’t visit Norway without learning about Roald Amundsen. Think of him as a Scandinavian Neil Armstrong … if Neil and a few cronies had engineered the moon landing all by themselves.

Amundsen and his team were the first humans to plant a flag at the South Pole, a big deal in 1911, in the days before air and motor vehicle exploration.

The bigger deal, however? He beat the British to the punch.

After seeing two statues of Amundsen in the Arctic Circle town of Tromsø, Norway, last month, Ted and I are continuing our love of polar exploration lore as we dig into Amundsen’s story. The affair began a few years ago when we chanced upon a copy of Endurance, the magnificent book that chronicles Ernest Shackleton’s 1915 British attempt to journey across the continent of Antarctica.

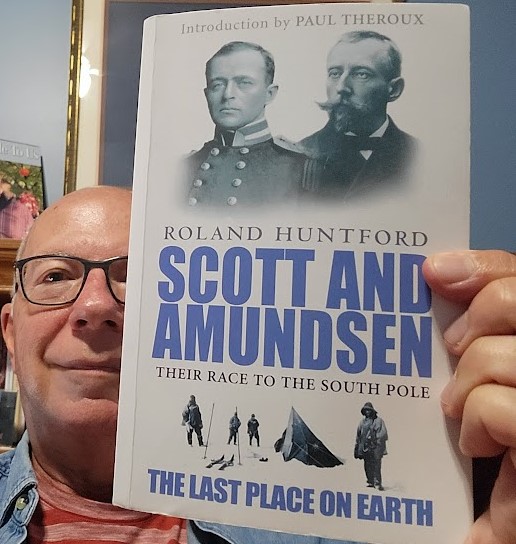

At the Polar Museum in Tromsø, we discovered another book, Scott and Amundsen: The Last Place on Earth, the suspenseful and detailed story of Amundsen’s race with a British team to find Antarctica’s heart, the South Pole.

And what a story it is: two men vying for glory in the last place on earth.

What was Amundsen doing in Antarctica?

The North Pole, closer to Amundsen’s Norwegian homeland at the top of the world, had already been reached by two Americans, so it was old news to Amundsen.

Besides, he’d been the first person to sail through the Northwest Passage, 900 miles of open ocean within the Arctic Circle, so he was ready to set his sights south … to the bottom of the world. And he was determined to claim the South Pole for Norway before the British got it, even though they had announced their quest before he did.

He knew he could do it … and was fairly certain the Brits hadn’t a clue.

He was right.

Scott and Amundsen: The Last Place on Earth recounts the story.

Any book with an intro by Paul Theroux has to be good, doesn’t it?

It is great, IMHO.

The book created controversy in the UK when it was first released in 1979. Why? Because it debunked the heroic myth around Robert Falcon Scott, the British naval officer who led the British journey to the South Pole. He and his team made it to the Pole not long after Amundsen did, but they all died on the treacherous return to their base camp.

The book strips away the years of patriotic devotion heaped on Scott.

In author Roland Huntford’s well-documented view, Scott was a bungler from the word go. Lazy, ill-prepared, full of himself while he blamed his subordinates for the team’s failure. If not outright racist, he was ethnocentric in his rejection of Eskimo techniques for surviving in the bitter cold. Who could know better than the Royal British Navy? Who indeed?

It all spelled death for Scott and four of his men, while Amundsen–smart, experienced in snow, ice, and sub-zero temperatures, willing to take the advice of others, and, above all, efficient in the way he prepared and led his team–skied safely back to Framheim, his base camp, without losing a man.

He almost made it look easy.

Writes Huntford: “Amundsen … was the rare creature, an intellectual Polar explorer; with the capacity to examine evidence and make logical deductions. And he had flair, talent, perception; possibly the elements of a genius.”

Study paid off for Amundsen.

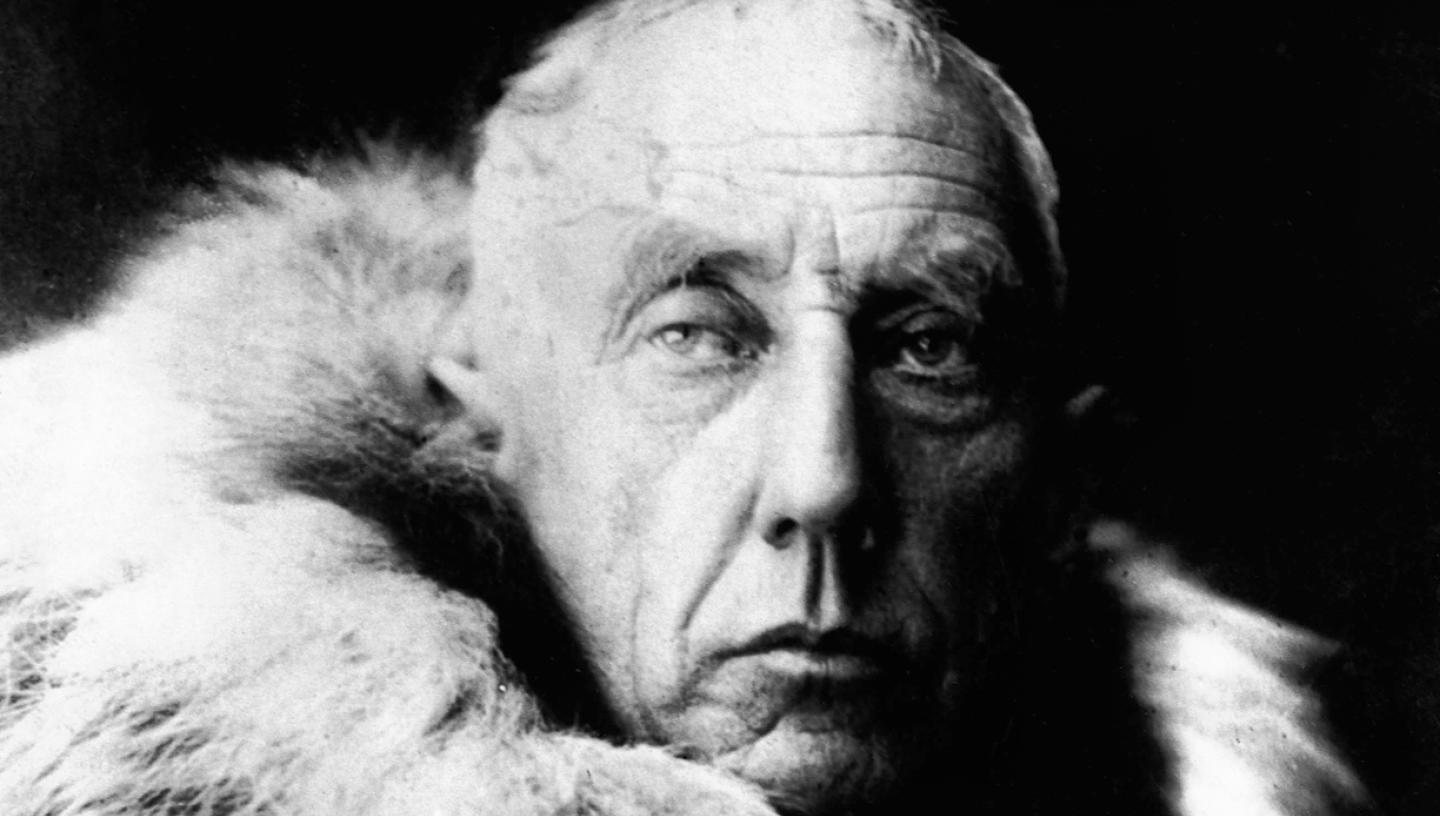

In the photo above, he’s decked out most likely in one of the cloaks he designed from the Eskimo mode of dress, where loose-fitting garments let in the air so sweat could evaporate … while Scott and his men were drenched and freezing in their tight-fitting clothing. He also wore furs, just as the Eskimos did.

He had better goggles, too. Again, Amundsen had them fashioned after the ones worn by the Eskimos, designed to shield out the sun’s glare and reduce fogging. On the other hand, Scott and his team were frequently snow-blind.

Lack of preparation was Scott’s undoing.

Scott also failed because he used ponies rather than sled dogs, and exhausted his men by having them pull 200-pound sledges on the journey rather than letting the huskies do it.

Scott and his team wore woolen clothing rather than furs, which are considered vital to Arctic and Antarctic exploration. [The chic number above is featured at the Polar Museum in Tromsø.]

Scott failed, too, because he hadn’t planned on enough provisions for his team on their return from the Pole to their base camp. They were hungry, suffering from the physical and mental effects of scurvy, plagued with frostbite … the list goes on.

They simply wore themselves out, thanks to a hapless leader.

The irony, Huntford points out, is that Scott became the hero once the race was over.

He wrote his journals in flowery prose that cast his and his team’s adventures as a brave and glorious attempt to beat the odds and score a victory for the British crown, while Amundsen’s journals were terse, matter-of-fact, efficient … in short, not very interesting reading.

The public devoured Scott’s book, while giving Amundsen’s a lukewarm reception. He suffered financially. Worse, many people the world over viewed him as an interloper, rudely snatching from the Brits the honor of being first to the South Pole.

In this case, it seemed humankind preferred a dead romantic hero to a living, pragmatic one.

It’s a fascinating story.

One I can’t seem to let go.

Maybe it’s the idea of all those hunky men snuggling together (which by all accounts they did) in their sleeping bags while icy wind roared outside their tents. But that scenario holds true for any polar discovery tale, regardless of the explorers’ nationality.

Maybe my Norwegian ancestry is speaking to me here. My dad’s Anglo-Saxon family I find nowhere near as fascinating as the Norwegians on my mother’s mother’s side of the family.

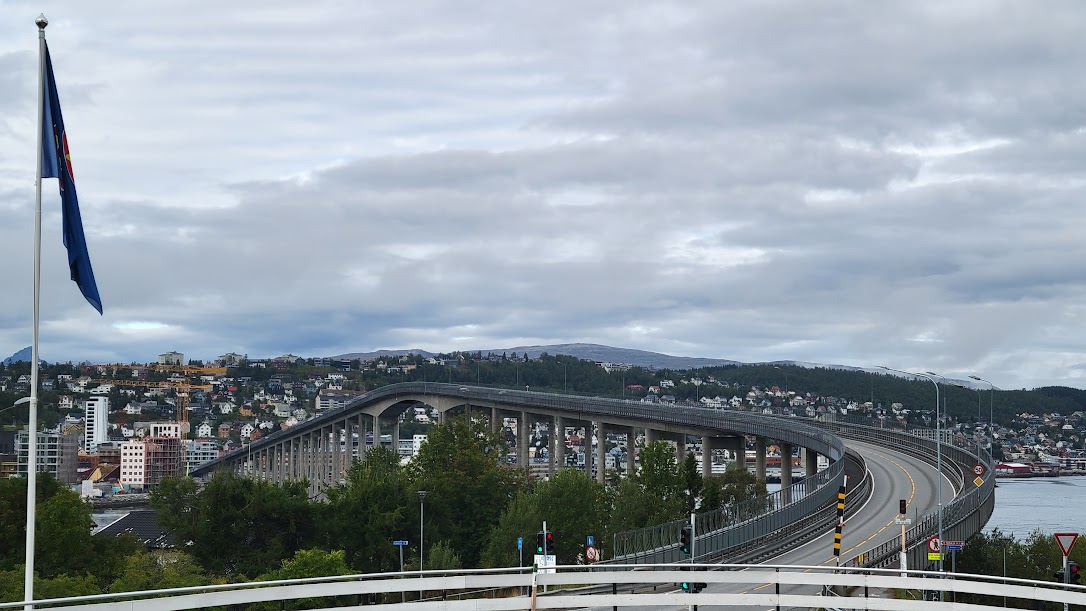

So I couldn’t help but feel proud last month when we visited Tromsø, a gem of a town in the far north of Norway.

Tromsø was Amundsen’s departure point before his seaplane went down in the fog over the Barents Sea on a rescue mission for a lost airship in the Arctic. It was his final adventure. The year was 1928.

Here’s a photo of Ted taking a break on one of our walking excursions in Tromsø.

And the bridge leading into the town.

I feel certain that my Norwegian ancestors, who were farmers and railroad workers in Minnesota during Amundsen’s heyday, followed his journeys while he made history for their native land.

I wonder how they shared his stories among themselves and with friends. Around the dinner table? Maybe at picnics on the grounds of their Lutheran church? Or huddled around a roaring fire in winter?

Whatever they were doing when they spoke of Amundsen, I feel certain the crafty explorer made them proud to be Norwegian, too.

[Note: I retrieved the above photo of the Amundsen team at the South Pole from Cool Antarctica, October 2, 2023. Credit for the marvelous black and white photo portrait of Amundsen at the top of this blog goes to the Royal Museums Greenwich, retrieved from its website on October 2, 2023. And a special credit and thank-you go to Mark Wallace Maguire, my explorer-spirited Atlanta friend who planted the seed for my fascination with all things Amundsen.]

Great read! Thanks.

Martin Martin C. Lehfeldt Former President, Southeastern Council of Foundations Writer and speaker in the not-for-profit sector

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Martin!

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this and knowing the record was set straight. We enjoyed being in Tromso in March 2022, but didn’t get to stay long. Safe travels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Deanna. We thought four nights in Tromso might be too much, but we found lots to see and do the whole time we were there. Glad you enjoyed the post. It is an amazing story. Stay well!

LikeLike

This was interesting and entertaining. We are looking forward to 5 nights in Tromso starting June 13.

LikeLike

Thanks! I look forward to hearing your perspective. Enjoy. We would go back in a heartbeat. Mike

LikeLike